Teaching a Humanoid to Walk

We trained a locomotion policy that got our humanoid robot Asimov to walk.

We trained a locomotion policy that got our humanoid robot Asimov to walk.

We focus less on algorithms and more on what information the policy is allowed to see, when, and why. We outline how we structured the observation space, why the critic has access to privileged signals that are intentionally hidden from the actor, how our reward design diverges from common open-source baselines like Booster Gym, and the lessons that emerged from running the policy on real hardware.

Locomotion as a Data Interface Problem

Our locomotion policy is a standard feedforward network. What mattered was not the architecture, in this case a simple MLP, but the contract between the policy and the system it controls.

Early on, we observed that the robot oscillated violently on startup. We needed to understand why the policy learned to oscillate. After deep analysis, we realized the policy was behaving like an underdamped control system.

This led us to reframe the entire locomotion problem. We did not spend much hand-shaping the RL rewards around walking in simulation. Instead, we spent time investigating what data the policy needed to see during training, so it generalizes to real hardware.

Observation Space: Dropping Ground Truth Variables

Our policy observes data in 45 dimensions:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ ACTOR OBSERVATIONS (45D) │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ base_ang_vel (3D) - IMU angular velocity │

│ projected_gravity (3D) - Which way is down │

│ command (3D) - vx, vy, ωz targets │

│ joint_pos_group1-3 (12D) - Joint positions │

│ joint_vel_group1-3 (12D) - Joint velocities │

│ actions (12D) - Previous action output │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘Notice what’s missing: base linear velocity (V_x, V_y, V_z).

Many open-source locomotion codebases feed ground-truth linear velocity to the policy. We actually didn’t do this. Why? Because on the real robot, you don’t have ground-truth velocity. You have an IMU that drifts, encoders that measure joint positions, and nothing else.

If you train with perfect velocity information, your policy learns to rely on it. Then it fails on hardware where that information doesn’t exist.

Staggered Observation Delays: Matching CAN Bus Timing

On a real robot, we read motor states over CAN bus. The motors are polled sequentially, not simultaneously. This means hip motors report data that’s 6-9ms stale by the time ankle motors report.

Most simulators ignore this. Every joint gets perfectly synchronized into zero-latency observations. The policy trains on pristine data, then fails when real data arrives out of order.

We modeled CANBus latencies explicitly:

# CAN read order creates timing skew

JOINT_GROUP_1 = ("hip_pitch", "hip_roll") # Read first → 6-9ms stale

JOINT_GROUP_2 = ("hip_yaw", "knee") # Read middle → 3-5ms stale

JOINT_GROUP_3 = ("ankle_pitch", "ankle_roll") # Read last → 0-2ms fresh

# Each group gets different observation delay

"joint_pos_group1": delay_min=0, delay_max=2 # 0-10ms randomised

"joint_pos_group2": delay_min=0, delay_max=1 # 0-5ms randomised

"joint_pos_group3": delay_min=0, delay_max=0 # Fresh dataThis is different from typical domain randomization. We’re not adding random noise for robustness. We’re intentionally modelling our training environment to match the TYPE and TIMING of data the policy will face in real life.

Asymmetric Actor-Critic: Teaching Through Privileged Information

During training, the actor only sees what the robot’s real sensors provide. The critic, however, has access to additional privileged information. This approach, called Asymmetric Actor-Critic, lets the policy learn to infer quantities it can’t directly observe.

What the Critic Sees

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ CRITIC OBSERVATIONS (Privileged Info) │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Everything the actor sees, PLUS: │

│ │

│ base_lin_vel (3D) - Ground truth velocity │

│ foot_height (2D) - How high are the feet │

│ foot_air_time (2D) - Time since last contact │

│ foot_contact (2D) - Binary contact state │

│ foot_contact_forces (6D) - Ground reaction forces │

│ toe_joint_pos (2D) - Passive toe position │

│ toe_joint_vel (2D) - Passive toe velocity │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘The Critic Sees the Toes

Asimov has passive spring-loaded toes. They deflect under load but have no motor and no encoder, which means the robot doesn’t “sense” the toes. You can read more about this design decision here:

By exposing toe state to the critic, the policy learns the relationship between toe behavior and stability, inferring it from ankle positions and IMU readings during deployment.

# Critic sees toe state (privileged info)

"toe_joint_pos": ObservationTermCfg(

func=mdp.joint_pos_rel,

params={"asset_cfg": SceneEntityCfg("robot", joint_names=TOE_JOINTS)},

scale=1.0,

)

"toe_joint_vel": ObservationTermCfg(

func=mdp.joint_vel_rel,

params={"asset_cfg": SceneEntityCfg("robot", joint_names=TOE_JOINTS)},

scale=0.1,

)The same principle applies to contact forces. The actor learns to “feel” the ground indirectly from joint positions and orientation. This improves stability and encourages more effective push-off while walking, even without direct force sensing.

Our current policy doesn’t instantaneously react to changes in ground contact force, like Unitree’s G1. Conversely, we observed quieter, more controlled footsteps when the robot was destabilized, a phenomenon we plan to study and improve further.

Improving Rewards

For rewards engineering, we were heavily inspired by Unitree, Booster Robotics, and MJLab’s existing open source rewards, and for the most part, kept the physics simple.

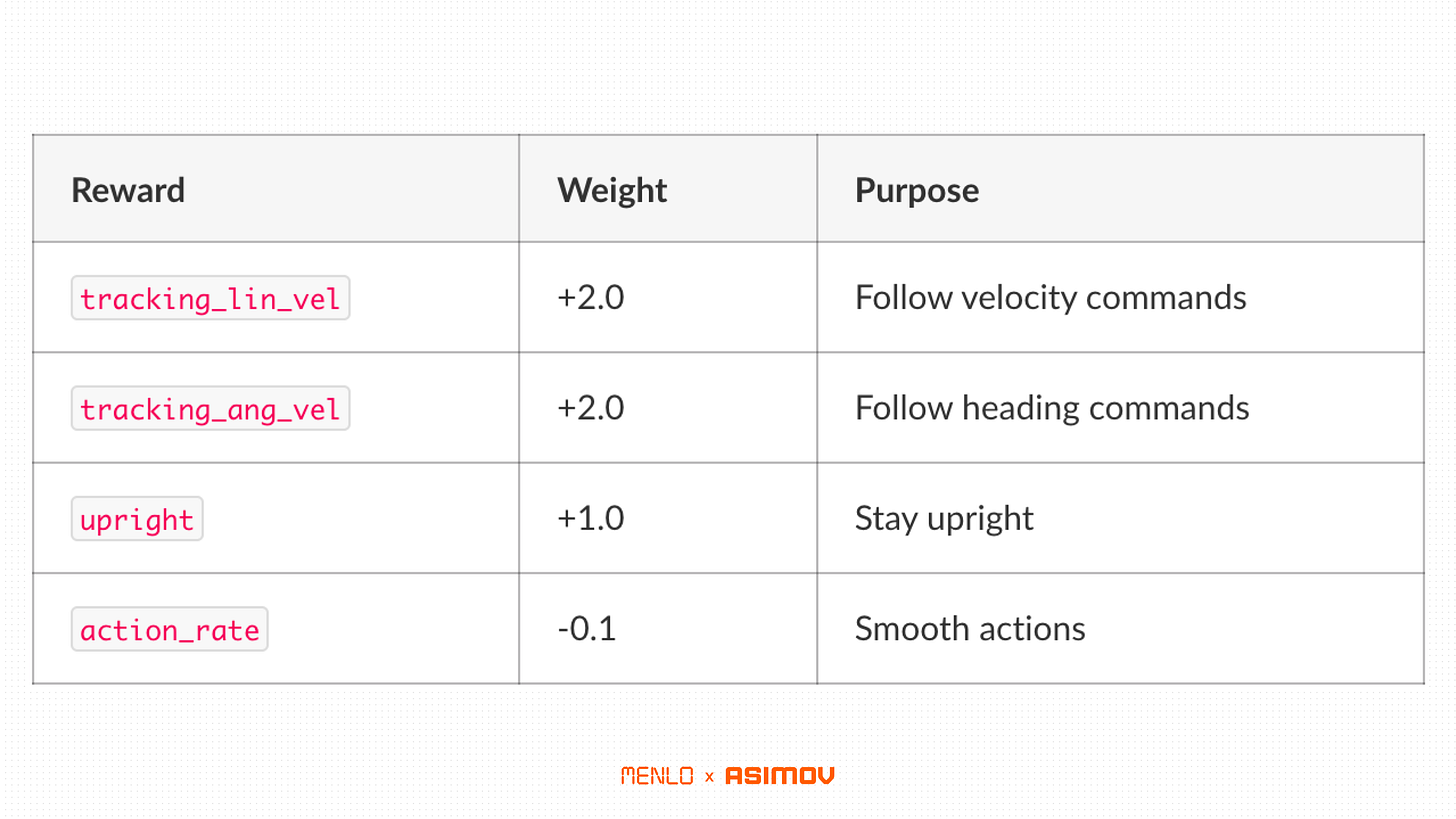

Of course, we made some deletions and additions per Asimov’s custom hardware. For example, we kept the following:

We made the following changes

1. No Gait Clock because all humanoids stride differently

Booster uses an explicit gait clock—sine/cosine phase signals that tell the policy “now is when the left foot should swing.”

# Booster's gait clock observation

cos(2π × gait_process), # 1D

sin(2π × gait_process), # 1DWe don’t use this. Our policy discovers its own gait frequency from the velocity command and body dynamics. This makes the policy more flexible but potentially less sample efficient.

Asimov has unusual kinematics (canted hips, backward-bending knees, limited ankle ROM). We wanted the policy to find gaits that work for this robot, not impose a human-designed gait structure.

2. Asymmetric Pose Tolerances because all humanoids have different flexibilities

Booster uses uniform pose tolerances across joints. We use asymmetric tolerances tuned to Asimov’s mechanical design:

std_walking = {

"hip_pitch": 0.5, # Large variance - canted hip design allows wide range

"hip_roll": 0.25, # Moderate - asymmetric joint limits

"hip_yaw": 0.2, # Standard

"knee": 0.5, # Large variance - knees extend backwards

"ankle_pitch": 0.2, # TIGHT - only ±20° ROM

"ankle_roll": 0.12, # TIGHT - only ±15° ROM

}Asimov’s ankles have limited range of motion (hardware constraint from the parallel RSU mechanism). If we used large pose tolerances everywhere, the policy would try to use ankle ranges that don’t exist and fail on hardware.

3. Narrow Stance Penalties

Asimov has a narrower stance than most humanoids (~21cm stance width). This makes lateral stability harder. We increased penalties for:

"body_ang_vel": -0.08 # Pelvis rotation (was -0.05)

"angular_momentum": -0.03 # Global stability penalty

4. Contact Force Limits

We penalize excessive ground reaction forces:

This teaches the policy to place feet gently rather than stomping. Important for hardware longevity.

5. Air Time Reward

Asimov is light (~16kg legs). It can actually achieve flight phase during walking. We reward air time:

"air_time": +0.5This encourages dynamic gaits rather than shuffling.

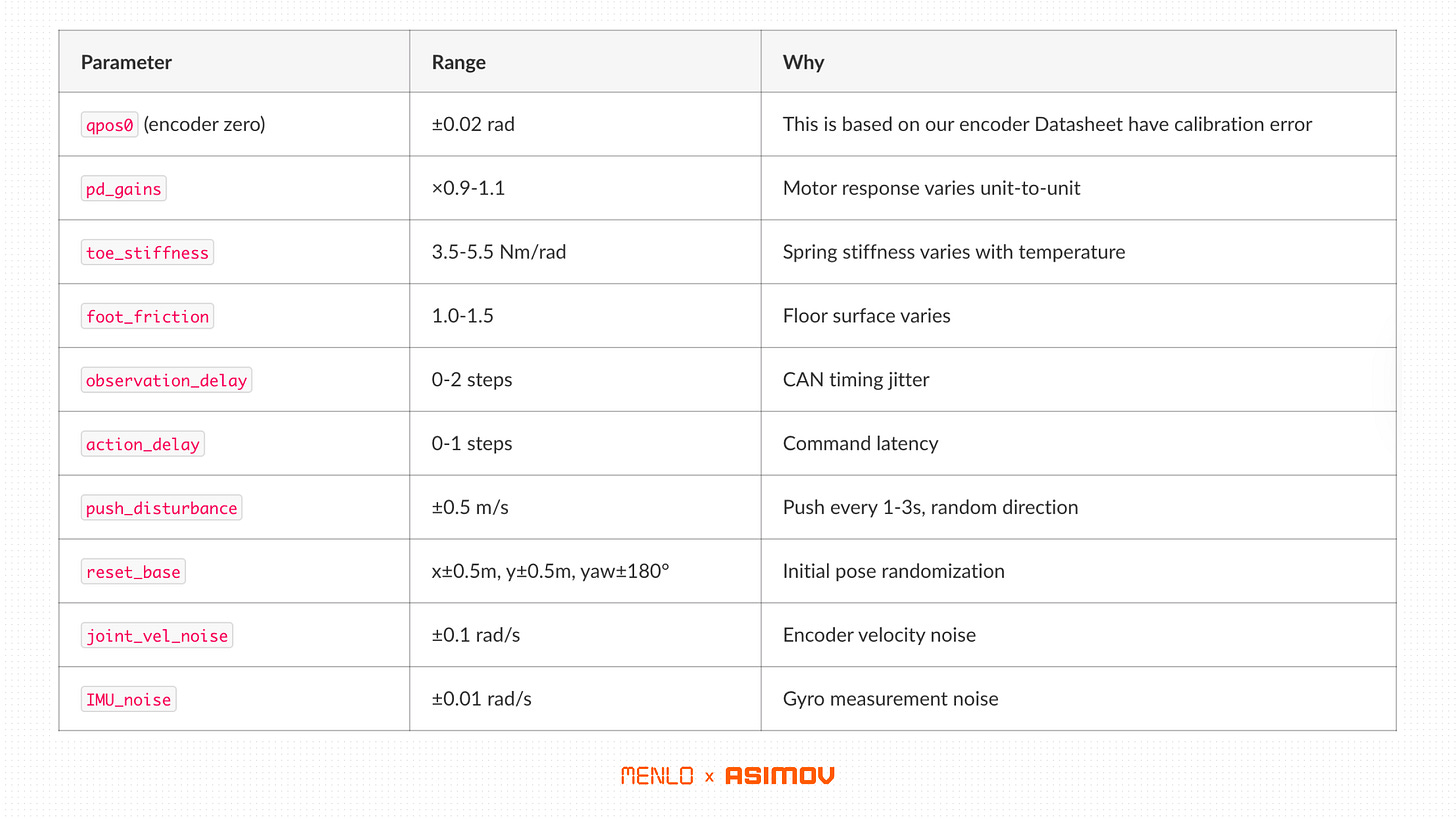

Domain Randomization: Targeted, Not Broad

We didn’t randomize everything, like mass, friction, gains, delays, and noise.

We took a more targeted approach towards robustness. We randomized the specific parameters that we knew differed between sim and real, based on our hardware characterization.

What We Randomise

What We intentionally did not randomize

Body mass: Disabled for initial learning. Adding ±20% mass randomization made training unstable. We’ll add it in later for robustness fine-tuning.

Link lengths: Our URDF matches the real robot accurately. There was no need to randomize geometry.

Gravity: It’s 9.81 m/s² everywhere we deploy.

The philosophy for this initial policy was to randomise what you know varies, and don’t randomise what you’ve already measured accurately.

Network Architecture and PPO

Actor-Critic Networks

Actor: obs(45) → 512 → 256 → 128 → actions(12)

Critic: obs(45) + privileged(~20) → 512 → 256 → 128 → value(1)

Activation: ELU

Observation normalisation: Enabled

Initial noise std: 1.0Three hidden layers with decreasing width. ELU activations throughout. Nothing fancy.

PPO Hyperparameters

learning_rate = 1e-3 # Adaptive schedule

gamma = 0.99 # Discount factor

lam = 0.95 # GAE lambda

clip_param = 0.2 # PPO clip

entropy_coef = 0.01 # Exploration bonus

num_learning_epochs = 5 # Epochs per rollout

num_mini_batches = 4

desired_kl = 0.01 # Target KL for LR adaptation

max_grad_norm = 1.0 # Gradient clipping

num_steps_per_env = 24 # Rollout lengthCompared to Booster (learning_rate=1e-5, mini_epochs=20), we use higher learning rate and fewer epochs. Our adaptive schedule reduces LR when KL divergence exceeds target.

What We’re Working on Next

Terrain Curriculum: Currently training on flat ground. Next step is procedural terrain with curriculum learning, start flat, progressively add slopes, stairs, and rough terrain as the policy improves.

Velocity Curriculum: Our current velocity range is conservative (±0.8 m/s forward, ±0.6 m/s lateral). We’ll expand this with curriculum learning once flat-ground performance is solid.

Full Body Integration: The legs work. Now we’re integrating with arms and torso for the complete 26-DOF+ humanoid.

You can read more about how we designed the hardware and firmware in other posts in this series:

Menlo Research is building and open sourcing an autonomous Humanoid from scratch. It has a modular design, with the legs, arms, and head development happening in parallel. We build in public and share our wins (and failures on most days) openly. You can also follow us on X, Instagram, and YouTube.